By Carol Vaughn —

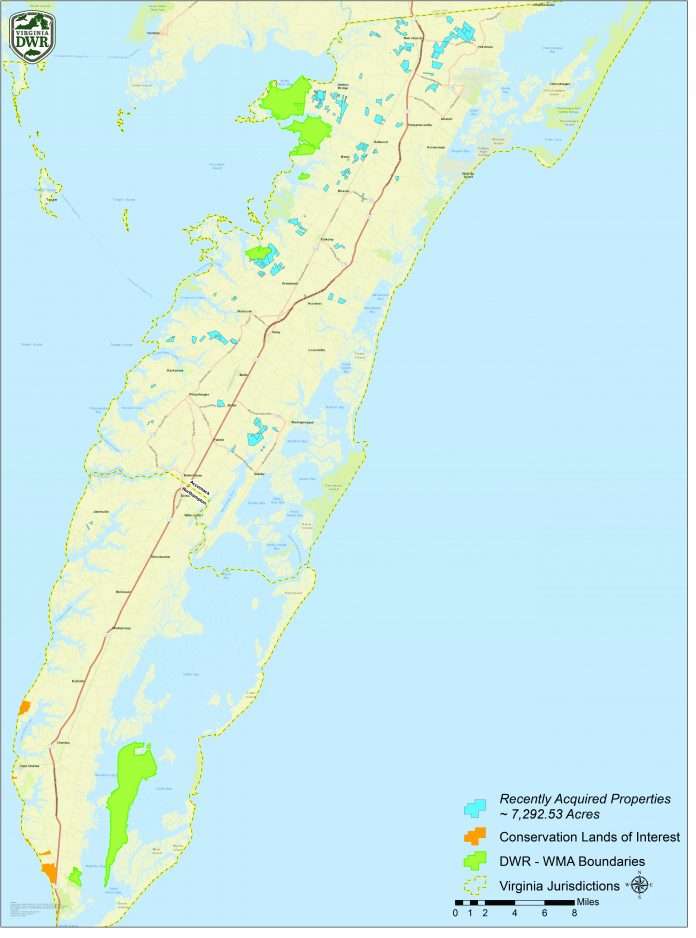

More than 8,500 acres on the Eastern Shore are being acquired by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources for conservation and wildlife management.

All but two small parcels near Jamesville are in Accomack County, with large amounts of acreage located in the northern third of the county.

DWR staff heard comments about the acquisition from nearly three dozen speakers in a standing-room-only meeting Wednesday at Eastern Shore Community College.

Adjoining property owners spoke about concerns over existing rights of way and potential trespassing by visitors to the public lands.

Hunters asked questions about regulations, access, and safety.

Some speakers thanked the department for conserving the land and asked about volunteer opportunities.

Others were concerned about loss of tax revenue to the counties.

The second phase of the acquisition, totaling around 6,875 acres, is set to happen this month.

DWR in an earlier phase acquired 1,043 acres in the Doe Creek area, near Onancock, in January.

A smaller, third phase, including around 625 acres in Northampton where parcels need additional research, is expected to close early next year.

The properties formerly were owned by Chesapeake Corporation, a paperboard container manufacturing company.

The land was purchased in 1999 by The Conservation Fund, an environmental nonprofit organization, according to Rebecca Gwynn, DWR deputy director.

The land was appraised at $9.1 million and The Conservation Fund donated 10% of that amount as part of the purchase by DWR and its partners, Gwynn said. The project’s total cost is around $13 million, which includes surveying and other expenses.

“We still need to look at each of these parcels, specifically the people who live around it, and make sure we understand what it can accommodate from the perspective of number of users at any one time and what types of uses and activities will be appropriate,” Gwynn said in answer to questions about what public uses will be allowed.

Information about allowed activities for specific properties will be available on the DWR website, she said.

Asked about DWR’s long-term plans for additional land acquisition, Gwynn said, “We are somewhat strategic, but this was an opportunity, kind of, of a lifetime for us to make this kind of a purchase from The Conservation Fund … to improve habitat for migratory birds here on the Eastern Shore and really help contribute, we think, in a positive way to help our recreation on the Eastern Shore.

“I don’t have a specific plan in mind right now (for additional acquisitions). We’ll look, on maybe some of these parcels, to expand out if the opportunity presents itself, if there is another willing landowner — but I don’t have a secret plan back at the office that says we’re going to triple this.”

A state law that requires DWR to return 25% of timber proceeds to the locality will help offset the loss of real estate tax revenue to the county, Gwynn said.

The plan is to harvest industrial pine from the properties and replace it with vegetation that is better wildlife habitat, she said.

Additionally, “We think there is great opportunity to work with the Eastern Shore tourism alliance and the chambers of both counties to also talk about how we can collaborate in expanding promotion of the Eastern Shore as an outdoor recreation destination, with these parcels kind of serving as a foundation,” she said.

The Eastern Shore properties will add to Virginia’s wildlife management areas, which at present include 48 WMAs totaling more than 230,000 acres.

The land will be managed for native wildlife and habitat, including increasing habitat for migratory songbirds, according to Matt Kline, DWR Region 1 lands and access manager.

The acquisitions will help Virginia meet its Wildlife Action Plan goals for species on the Shore.

Of Virginia’s 883 species with greatest conservation need, 79 are thought to be on the Eastern Shore, according to Kline.

Of the 79 species, 67 are dependent on habitats provided in the DWR’s planning region and are considered a priority for conservation. Those include the black rail, the American woodcock, and the black-throated blue warbler.

Conserving and managing the land for wildlife also will help the region prepare for climate change and sea-level rise by keeping the land free from buildings and able to be adapted more easily as the sea level rises, according to David Norris, DWR Regional 1 regional wildlife manager.

“These are 60-some parcels that are not going to have a house on them,” he said.

The land also will provide recreational opportunities, including hunting and other uses.

“We want to get these properties open as soon as possible,” Kline said, but he noted some of the property needs to be timbered first and access, parking, and other infrastructure has to be installed.

Some areas could be open to the public as soon as this spring, in time for turkey gobbler hunting season, according to Kline.

Kline said the department is working to be consistent in its regulations for use of WMAs on the Shore, noting a lack of consistency is the number one complaint DWR hears from the public.

Kline said DWR manages the number of visitors to a wildlife management area in part by limiting the number of parking spaces at access points. Only foot and bicycle or E-bike traffic are allowed within WMAs, he said.

Gwynn said DWR law enforcement officers “stand ready” to address trespassing onto adjoining privately owned land.

DWR is seeking volunteers to assist with the wildlife management areas on the Shore. Apply to volunteer at https://virginia.volunteers.kalkomey.com/accounts/sign_in