By Arthur King Fisher

Special to the Eastern Shore Post

In 1991 this writer interviewed his two elderly cousins, Virginia Carmine and Josephine Metcalf, both of Onancock, concerning their recollection of hog killings on the Eastern Shore during their youth, which were the years immediately following World War I.

Adults would get up at 3 a.m. to begin a very long day’s work; however, the Metcalf sisters, Virginia and Josephine, and the youngest Fisher daughter, Bernice (Scott) were allowed to stay in bed until 5.

Hog killings were held on Mondays in December and the schedule rotated among the four sisters and their husbands: Dottie Fisher Belote and husband Claude; Minnie Fisher Bloxom and husband Gordon; Lillie Fisher Metcalf and husband Howard; and Jewel Fisher Hickman and husband Will.

Bloxom, Metcalf, and a hired man would get the hogs down and cut their throats, no small task because the animals sometimes weighed 500 pounds. One man would grab the hog by his hair and throw him on his side. Then the hog would be turned on his back and stabbed.

Next he was put in a scalding cask. (The water was considered hot enough for the task if a corncob stuck in it was so hot that you could barely squeeze it; then the corncob was placed in the hog’s mouth.)

The hog was then scraped with a tool appropriately named a hog scraper and clam or whelk shells. It was then hoisted on crotches, a three pronged arrangement, and there gutted. The insides were pinkish and almost transparent.

It was Minnie Bloxom’s job to clean the intestines, which became the casings for sausage. The liver, lights (lungs) and heart were hung up on a clothesline. It was the men’s jobs to cure the shoulder and hams with salt, saltpeter, and pepper to pickle the spareribs.

The cuttings from the hambone became mincemeat when mixed with beef, raisins, orange peelings, and currants.

Josephine and Virginia recalled the group of women in “the old kitchen.” (It was a custom for Eastern Shore homes in the eighteenth century to have a kitchen separate from the residence for fire safety reasons. Many of these were still standing in the early twentieth century but were mainly used in the latter century for hog killings and for laundry.) In addition to the sisters, help in the kitchen consisted of grandmother Mary Josephine Wessells Fisher, great-grandmother Hettie Bloxom Fisher, and two hired women. Grandmother Fisher would put the cut-up fat meat (lard) in an open pot in the fireplace of the old kitchen, where it cooked for half a day.

Frying lard was another important task of a hog killing. The women would take the fat meat from the iron pot when it had become lard and use it for cooking for the next twelve months. (There was no Crisco then.) Children enjoyed the “cracklins,” little pieces of lard that had been fried.

Because there was no refrigeration, the tenderloin was cut into strips and canned. Pork chops also were canned and put on a pantry shelf. Some people used cold packing. Hog jowl was used for seasoning and was thought to be especially good with turnip greens, which was the favorite green vegetable of Eastern Shoremen of 80 years ago.

The men and women who took part in the activities on hog killing day ate well and heartily. About 7 a.m. after the hogs had been hung up, a big breakfast was served consisting of hotcakes, eggs, sausage and fig or strawberry preserves.

The midday or afternoon meal was chicken and dumplings, the omnipresent turnip greens, cabbage, fruit, and two kinds of dessert, usually coconut and pound cakes made by Jewel Hickman.

The afternoon chores included cooking the liver, lights, and heart on the stove with sage, pepper, salt, flour, and meal added. The resulting scrapple would be cut in blocks.

Also in the afternoon the sausage was ground and mixed with sage and pepper. The sausage was hung in links in the smokehouse.

Companion” published 1901, available at the Eastern Shore Public Library.

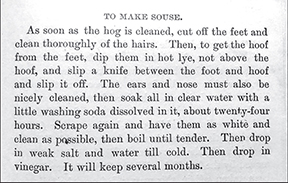

Pickled souse also was prepared. Today’s Eastern Shoremen probably do not know what souse is; so let the record show it was made from the nose, ears, and feet of the hog. Virginia and Josephine recalled that it was hard to clean but when eaten with Hayman potatoes it was good.

This “souse cheese” also was a product of hog killing. The head was boiled and peeled yielding a gelatin-like substance, which had to be soaked for twenty-four hours before being put into stone jars.

At about 4:30 p.m. the tired Fisher sisters, husbands, and children would head home. Precious little of the hog had been wasted.

A campaign is underway to fund the new ESVA Heritage Center. Those wishing to donate or to be recognized with other Founders of the Heritage Center should send donations to ESPL Foundation, P.O. Box 554, Accomac, VA 23301, call 757- 787-2500, or visit www.shorelibrary.com