By Stefanie Jackson – Kinsey Tedford, a Ph.D. student at the University of Virginia, is originally from Oklahoma but was drawn to the Eastern Shore by her love of the outdoors, interest in wildlife ecology and conservation, and pursuit of a career in marine biology.

She received both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology from the University of Central Oklahoma. Tedford’s first experience with The Nature Conservancy was at the Oka’ Yanahli Preserve, which protects the Blue River of Oklahoma.

She began working on the Eastern Shore in 2018 and applied for the Virginia Sea Grant. She spoke with Bo Lusk, who is known for his work with TNC, and was accepted into the program.

Now, through her field research on oyster reefs, Tedford is part of the partnership of TNC’s Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve and UVA.

She anticipates that her studies of oyster reefs will help TNC identify areas for future oyster reef restoration projects.

Restoration efforts can include the placement of hard shell that mimics an oyster reef and building oyster castles. Oyster castles are reef-like formations that can be built out of concrete blocks made from a special concrete mix that attracts baby oysters, called oyster spat.

Oysters are known as filter feeders, meaning they filter their food out of the water through their gills. Since they prefer to eat algae and other types of phytoplankton, they may be helpful in preventing the growth of algal blooms.

Stormwater runoff and wastewater treatment facilities can introduce too many nutrients into the water, promoting the growth of algal blooms. These can be harmful in several ways.

For example, after algae dies, the decay process deprives marine plants and animals of oxygen. Algal blooms also block sunlight from marine plants that need it to make food.

Oysters often will take in sediment along with their food. After oysters digest their food, they expel both feces and the undigested sediment, called pseudofeces, which typically settles to the bottom and is harmless.

Oyster reefs provide habitats for small animals like grass shrimp, mud crabs, and barnacles, which serve as food for larger animals like blue crabs, striped bass, and black drum.

Oysters also encourage plant growth by filtering the water and making it clearer by removing nutrients and sediment. One adult oyster can clean about 50 gallons of water per day.

According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, there once were enough oysters in the Chesapeake Bay to clean its waters every week, but now there are so few oysters it would take them a year to do the same job.

Among the many economic and ecological benefits of oyster reefs, they also are the “first line of defense” against storm surge, Tedford noted.

Oyster reef restoration can be a time-consuming and costly process, so it’s important to identify where oysters will grow and thrive best. That’s where researchers like Kinsey Tedford come in.

Her work is focused on oyster recruitment, survival, and growth.

Her studies take her as far north as Hog Island, as far south as Wreck Island, and toward the mainland.

It can be challenging for oysters to find a “sweet spot” to survive and thrive. Some areas are good for recruitment but not survival, and the reverse is also true, Tedford said.

Every summer the oysters spawn, the process by which they reproduce. They float in the water and eventually wind up on a reef.

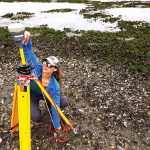

Tedford attempts to determine which areas are best for oyster recruitment by selecting areas to set out tiles that mimic the base of an oyster reef, then she checks back later to count how many oysters have been recruited to the tile.

The tiles are used because it’s much easier to get an accurate oyster count on a tile than on the reef. Each tile is about four inches wide.

Tedford photographs the tiles every month and uses computer analysis to measure oyster growth. Her research involves lots of photographs, measurements, and drawings.

Oysters don’t like still water, because they need some wave action to bring in oxygen and nutrients, but they don’t like heavy waves, either.

Large waves carry along with them excess sediment and fossilized bits of shell, which can clog up the openings of the oysters and prevent them from breathing. The oysters need just the right amount of wave action, which they often find near the mainland.

Tedford has observed that oysters prefer a narrow range of elevations; on the Eastern Shore, they typically prefer intertidal areas, in which they are exposed for about half the day, as opposed to subtidal oysters that are always underwater.

One area of interest right now is the Hillcrest Oyster Sanctuary, one of at least a half dozen oyster sanctuaries established in Accomack and Northampton counties by the Virginia Marine Resource Commission.

This oyster sanctuary begins in Brockenberry Bay, which can be seen from the Edward S. Brinkley Nature Preserve in Northampton County.

The Hillcrest Oyster Sanctuary is performing well and notable for its lesser waves and many mud flats. There are lots of adult and baby oysters there, and recruitment is significant.

Threats to their survival can include oyster harvesting pressures, although they are not too high on the Shore, Tedford noted. She also has little concern about nutrient runoff and pollution because of the Shore’s high water quality.

The question remains of how to find an ideal location for oysters to live, grow, and thrive, but with every photograph, measurement, and drawing, scientists like Tedford get a little closer to an answer.

Tedford anticipates that her research will help TNC maximize its resources for restoring oyster reefs.

She also hopes sharing part of her story will help in “teaching the community why science is important” and raising awareness about “how beautiful the place we live in is and how we can protect it.”

Click on a photo below to view it in full size.