By Carol Vaughn —

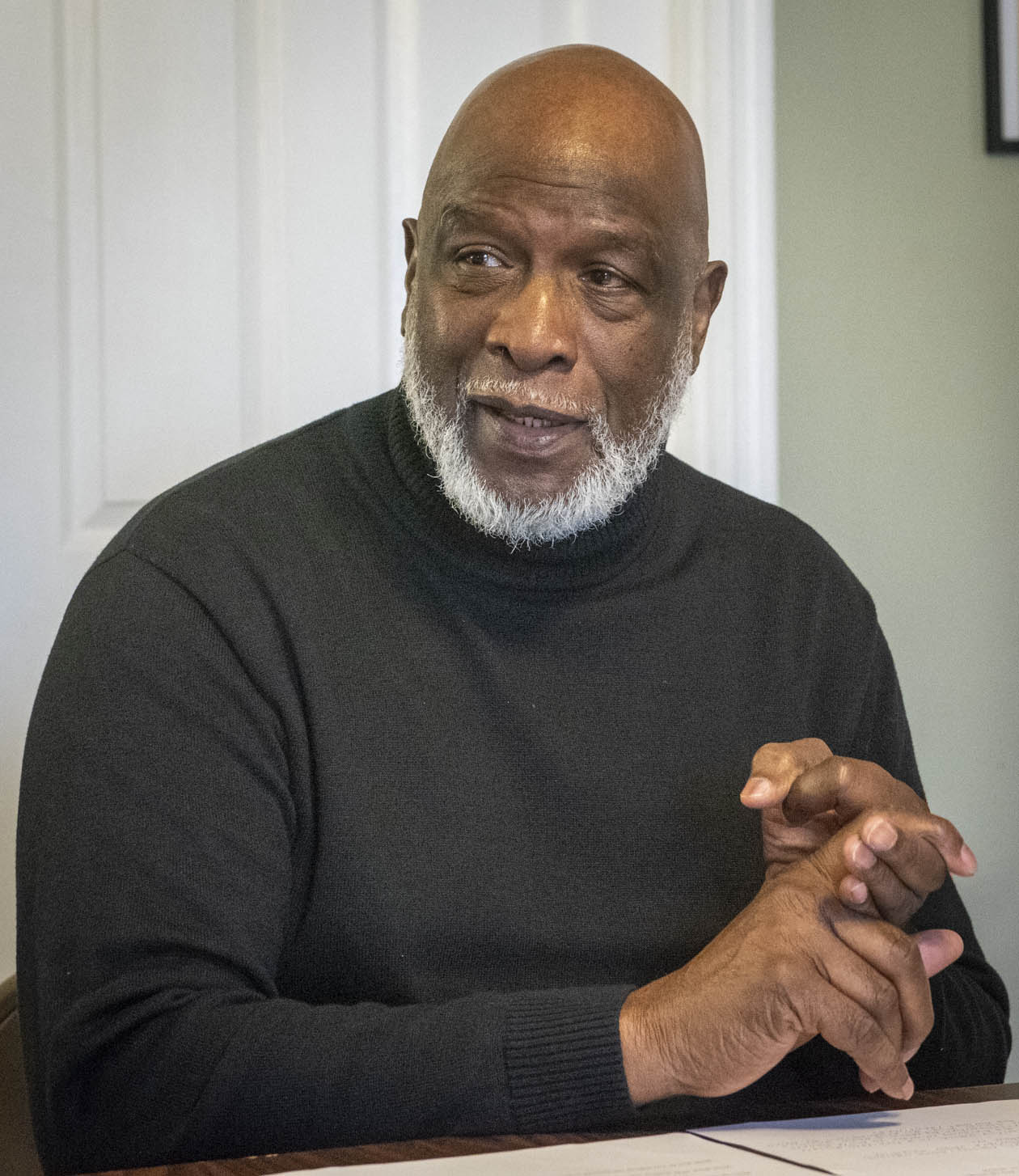

Gerald and Polly Boyd returned to the Eastern Shore, where Gerald grew up, in 2014 after a lifetime spent working for civil rights, social justice, and individual empowerment.

Still, the couple, married since 1969, did not come back to retire.

Polly, a licensed clinical therapist, and Gerald, who holds a master of divinity in transpersonal psychology and several certifications, including life coach, mediator, alcohol and drug counselor, anger management specialist, and others, are co-founders of Peacewerks Center for Well-Being and Eastern Shore Training and Consulting, Inc., both in Exmore.

Their stated purpose is to reduce the impact of poverty on the lives of Eastern Shore residents.

Gerald has worked in the fields of applied sociology, education, human development, and addiction recovery for more than four decades.

Polly has worked in a variety of community service fields for more than 50 years.

Gerald, who is Black, was born in 1943 in Mobile, Ala. His family traveled to the Shore as migrant farm workers, working mainly on the Hastings farm in Johnsontown.

His mother, Irene Thomas Boyd Harmon, married Howard Harmon, a man from the Shore, and Gerald grew up in a humble home behind Johnson’s Methodist Church, surrounded by strong Black women “who raised me, who taught compassion and love and service.”

He attended Machipongo Elementary School and graduated from the segregated Northampton County High School in 1962.

After graduation, he returned to Mobile, where he became involved in the civil rights movement.

His knowledge of the movement stemmed from books he accessed at school.

“I was a reader. We were very poor, so we didn’t have much,” Gerald said.

His mother encouraged him “not to sit around and watch other kids eat” when he did not have a lunch at school, but to use the lunch hour to read.

The guidance counselor’s office at the high school was in the school library, where Gerald spent many lunch hours. She invited the young man to come in.

The office had a tall bookshelf that was the teachers’ reference library. That is where, Gerald said, “I got my hands on those books,” including the writings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy’s “Profiles in Courage,” and others.

In Mobile, he was mentored by men like civil rights leaders John LeFlore, Henry C. Williams, the first Black licensed welder in the city, and Freeman Pollard, author of “Seeds of Turmoil.”

“Our responsibility was to desegregate the public facilities in Mobile,” Gerald said.

The organization would give him and the others $5 and they would dress in their best clothes and go to Whites-only businesses downtown, “to sit in restaurants to be told we couldn’t be served.”

He later was drafted during the Vietnam War. As a conscientious objector, he was sent to Paris, where he worked encoding and decoding messages.

Polly Boyd’s background was quite different.

Polly, who is White, had a privileged youth, growing up in California, the daughter of progressive parents who were involved in the civil rights movement.

Polly was in college in 1968 when she heard about Dr. King’s murder.

“I just couldn’t stay in school,” she said.

She had become a member of the Baha’i faith and wrote to the Baha’i national youth office, asking to be sent to a service project in the South as a volunteer.

The project turned out to be one headed up by Gerald.

“I was a very naive 19-year-old. I thought I was going to go down to the South and show them how to live their lives,” she said.

Polly and her twin sister thought White people needed to take more responsibility in desegregation, leading Polly and several others to enroll in a Black college in Mobile.

“We are responsible for segregation and we’re responsible for desegregation,” she said.

“That trip at 19 to Mobile changed my life. I learned so much in that Black college about Black history,” Polly said.

Gerald and Polly were married in 1969 in California, one of few states where marriage between Blacks and Whites was legal at the time.

Her parents sent them a credit card to enable them to get from Alabama to California.

“it took us some doing to get our tickets and to get to the airport separately and to get on the plane separately,” Polly said.

Since then, the couple lived and worked in numerous states, including five years in California; a decade in Kansas City, Kansas, where Gerald had been recruited to work in a substance abuse program and where they continued with their community organizing and improvement activities; South Carolina, where Polly finally was able to finish her college degree; and Georgia.

They have seven children and 14 grandchildren.

Over the years, they visited family on the Shore many times.

They returned to the Shore, in part, because they saw a need to address problems here resulting from poverty and drugs.

“Every time that we would come (visit) and read the Post, we would read about drug busts,” Polly said.

They talked with the social services and community services board directors and and with Juvenile and Domestic Relations Judge Croxton Gordon, who is now retired, “about the situation and the resources, and discovered that, basically, poor people just did their time for drug busts; they did their time and got out and people with money paid the fine and got out — and there was no treatment,” Polly said.

The Boyds were working in Atlanta as therapists at the time.

“We knew that there were thousands of therapists there and that we were needed here,” Polly said.

Additionally, Gerald asked his friends to tell him what topic he talked about most, other than topics like inclusion and the like.

“They said, ‘Going home.’ … There was such a big desire on my part to come back here and offer up a hand,” he said, adding, “… I wanted to come back here because we have a few tools in our toolbox and learned a thing or two and wanted to come back here to offer those tools.”

Nowadays, the couple spend their days providing clinical therapy to individuals, families, and groups; providing training and supervision to mental health interns; and providing diversity, equity, and inclusion training to groups and organizations.

They currently are working with around a dozen interns.

Additionally, the nonprofit ESTACI offers a scholarship program and Empowering Women and Girls programs, among other programs.

ESTACI’s projects include the Eastern Shore Music and Soul Food Festival, Samuel D. Outlaw Blacksmith Shop Memorial Museum, and the Eastern Shore Black History Tour.

Gerald also serves in a number of volunteer positions, including as organizer and chairman of the board of directors of the Samuel D. Outlaw Blacksmith Shop Memorial Museum; board of directors member of the Eastern Shore Chamber of Commerce; leadership council member of Virginia Organizing; 200+ Men of Hampton Roads member; NAACP of Northampton County chairman of criminal justice committee; Northampton County Parks and Recreation advisory board member; board of directors member, ESVA Literacy Council; and board of directors member, Rosenwald School.

Asked what is important about Black History Month, Gerald Boyd wanted to share with readers this statement by author and activist James Baldwin:

“American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

Polly Boyd responded to the same question, saying. “As a White person, it’s important for us to look at our history and be honest about it. … We’re responsible for White supremacy; we’re responsible for healing ourselves, and connecting with each other to do that, and educating ourselves. Really, Black history and Indigenous history and all of the communities in our country should be a part of all our history year around.”

Asked what Shore residents can do to better recognize Black History Month’s significance, Gerald said, “Practice cultural humility, which is a lifelong process of self-reflection and discovery in order to build honest and trustworthy relationships by learning about another’s culture — but one starts with an examination of one’s own beliefs and cultural identities.”

Peacewerks Center for Well-being and ESTACI are at 3100 Main St., Exmore. The websites are https://www.peacewerkscenter.com/ and https://www.estaci.org/

The phone number is 757-656-3460.