Story and Photos by Jim Ritch –

West of Weirwood, overlooking a marshy island and meandering channel where Nassawadox Creek flows into the Chesapeake Bay, lie the nine buildings of Bayford.

At the center, in a dip in the road, surrounded by residences and docks, reigns the Bayford Oyster Company, the origins of which date to 1899 and the owner of which is only the third generation in charge.

Those generations weave through two families joined by the sweat of watermen’s brows.

Stories in Bayford unfold like fabric, rather than unspool like thread, as in one thing happened, then another.

They jump through an inspired array of flashbacks, to other family members, their farms, habits, friends, exploits, before returning to any story’s original point.

As far as anyone can remember, and “anyone” means the jury that meets daily around 5 p.m. outside the oyster company to catch up on happenings, plus Captain Bob Fears, a former waterman, former Exmore chief of police, and former Chincoteague tuna boat skipper. At 70, Fears held until recent years his master’s license for 100-ton inland/ocean vessels.

This jury believes Bayford to be the home of the Eastern Shore’s oldest oyster shucking house still in continuous use.

Its construction was in 1902, three years after Captain Roscoe Walker Sr. moved from Delaware and founded the oyster company.

He would go on to serve on the Northampton County Board of Supervisors.

Until the dwindling oyster harvests of the mid-1960s, the shucking house sheltered 20 shuckers, each wielding a wooden block and shucker’s tools.

As many as 12 to 15 workboats would have been tied up behind the shucking house to unload their catch.

Armed with culling hammers, the shuckers separated clusters of oysters. With shucking knives they carefully opened the shells, working on opposite sides of a sloped concrete table that still dominates the center of the shucking room.

Also tied up, just outside a side door, floated a “monitor,” wooden barges of varied sizes, but in Bayford typically about 14 feet wide and 40 feet long, said the current owner of the shucking house, H.M. Arnold.

In the monitor rose a daily pile of oysters too small to harvest and frequently still anchored to the shells of other oysters.

Able to live out of the water for only a day or two, they were quickly returned to submerged flats to grow.

On the opposite side of the shucking house steadily grew piles of empty oyster shells to be returned to the bay strategically each July and August. Then, oyster spat floated in the water, searching for shells on which to attach and grow.

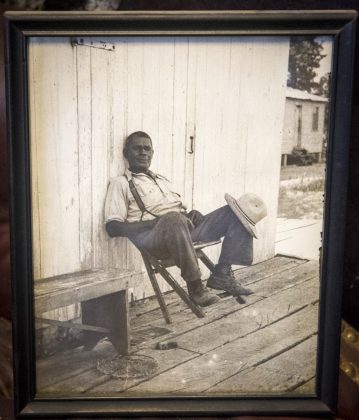

Captain Roscoe passed the company and shucking house to his son, “Hooksie” Walker, who partnered with a friend, Herbert “Redeye” Arnold.

Arnold earned his nickname because “every time he had a sip or two of whiskey, his eyes were red as a strawberry,” said Fears.

Hooksie and Redeye worked together in a joint venture until modern IRS rulings forced them to convert it to a company, but they kept the same name throughout.

The operation changed in the 1970s, when the oyster harvest crashed and the shucking stopped.

About that time, the two owners brought in Redeye’s son, H.M. Arnold.

Both Redeye and H.M. mixed work on the water with more shore-oriented occupations.

Redeye worked nights as a dispatcher for the Curtis Bay Towing Company in Norfolk.

He rode the bus from Nassawadox and back, trading crabs and oysters for passage to Norfolk.

“He could barter with anyone,” said H.M.

H.M. left a career working as a butcher at a grocery store in Exmore to join the oyster company, where his first major project was to help move the floats for shedding crabs indoors.

When the oyster harvests improved in the mid-80s, shuckers returned briefly to the building, although they moved to a smaller room that now serves as an entry foyer and office. Only two shuckers worked, the maximum then allowed by the health department.

Hooksie lived to be 92 and died only about five years ago, said Fears.

When he did, he left his share of the business to H.M., who is now the sole owner.

“H.M. was like a son to Hooksie,” said Fears.

And although the entire operation in the shucking house is now to shed soft crabs, H.M. keeps the company name: Bayford Oyster Company.

Some things just don’t change.

Today, tanks full of peelers and soft crabs fill half the shucking room floor.

Water sprays from overhead pipes, diffusing oxygen in the water and preventing the soft crabs from piling up on each other.

A new oyster tong lies across the concrete shucking table, and an encrusted “nipper,” a smaller version used in shallower water to harvest dark spots of oysters projecting from the bottom, hangs on the wall.

And music fills the shucking room from behind four glass tubes projecting from the front of a very antique radio.

Floods

Two or three times in a typical year, winds will whip out of the northwest and drive water into Nassawadox Creek, creating high tides that partially submerge the shucking house, said Fears.

The high water becomes a badge of honor in Bayford, where the high-water marks of outstanding floods are memorialized on the outside of the shucking house.

The highest was Hurricane Donna on Sept. 12, 1960.

The Wild Bear

Next to the shucking house, on slightly higher ground, is the former Bayford Post Office, which combined in one room a post office made up largely of a handful of cubbies for individual mail, plus a general store.

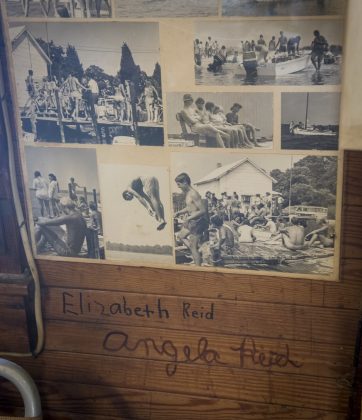

The wooden walls and attached photographs memorialize many of the residents, shuckers, and friends of Bayford, their names scrawled in ink.

The building is also a memorial to the Wild Bear Sandwich.

The sandwich, as prepared by Hooksie, grew in part from the limited kitchen space in the store, which was just a small corner of the one counter that ran perpendicular to the post office counter.

The sandwich was served cold and began with a “hobo bun” with raisins and frosting. It cost five or ten cents but was easily double the size of today’s sweet buns.

The bun was halved and filled with “rat cheese,” which came in circular boxes suggesting a wheeled shape and was very sharp in flavor, and spiced ham or rag bologna, said H.M.

The contents of the sandwich were weighed before being laid into the bun and charged by the pound.

So the assembled sandwich could cost 40 to 50 cents.

The Barge

Today, when Fears stands on the dock and surveys the creek, he sees roughly 30 docks that he built using his own pile-driving barge. Many of the docks were built for friends who supplied just the materials, companionship, and an appropriate supply of food and drink.

Fears also sees a day before the docks were built and only a few isolated houses lined the creek.

In those days, distance granted privacy, which one neighbor liked to enjoy by sunbathing on the roof of her house.

One day, the window banged closed behind her, trapping her, naked, on the roof.

While she pondered how she would re-enter the house, two Jehovah’s Witnesses came up her drive.

“She said, ‘Don’t look up here, but I need you to go inside the house and open the window,’ and then she went inside and got dressed,” said Fears.

Behind Fears today lies the rusting hulk of his pile-driving barge, run ashore and stripped of its heavy dual-drum winch and virtually every bit of equipment that can be sold.

When he started pile-driving and first assembled the barge in all its glory, he named it the “Herbert Arnold” after Redeye, who Fears says virtually adopted him into the family.

And to this day, Fears calls Redeye’s son, H.M., “brother.”

Highs and Lows of Soft Crabs

Soft crab prices peaked in New York City at $68 per dozen when this year’s season began, the highest price that H.M. Arnold has ever seen.

Prices plateaued at $58 per dozen and are currently between $30 and $35.

Today, jumbos sell locally for $35 a dozen; primes, $25 a dozen.

“That’s a decent price for here. I’ve had better and I’ve certainly had worse.

He has seen prices in the past as cheap as $10 a dozen.

The Last Frontier

As a sheriff’s deputy, Bob Fears often hosted county supervisors for ride-alongs in his cruiser, usually so that the supervisors could get a flavor for what was happening in the department.

On a night that J.T. Holland, then a supervisor and still owner of a Nassawadox insurance agency, was accompanying him, a call came that a man in a large labor camp had a gun and was going to shoot someone.

When Fears and Holland arrived, the man came to the door holding a .22-caliber rifle.

“You’d better lay that rifle down or I’m going to wrap that around your neck,” Fears said.

After the man put the rifle down and the commotion was over, Holland asked Fears if he wasn’t scared when he saw the rifle.

“No,” Fears said, “I looked it over and saw that it was a single-shot, and he had the barrel pointed at you.”

Some day, when Bob Fears and his gifted memory have passed from this planet, he intends for his ashes, plus those of his former close companion, a Jack Russell terrier named Rascal, to be spread from the Bayford dock.

“Bayford and Saxis are my two favorite places on the Eastern Shore, and they’re the last frontier, the way it used to be,” he said.