By Carol Vaughn —

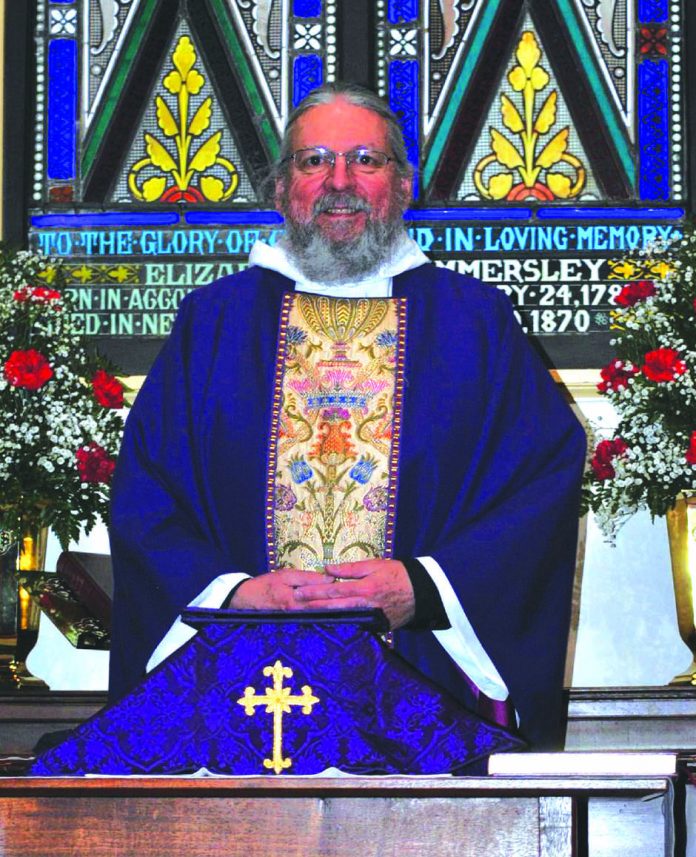

As Christians around the world prepare to celebrate Holy Week and Easter, the new rector of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Onancock reflected on the past year, ravaged as it was by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve experienced Lent for an entire year. … So, yes, we’re ready, I’m ready, for resurrection,…for new life,…lack of fear,” said Father Ed Hunt.

“So I think our ‘Easter,’ when it comes — whether it’s June or July or whatever — there’s going to be a lot of making up for stuff. There’s going to be all kinds of people gathering and food and barbecues,” he said, referring to the time when it will be safer again to get together as more people are vaccinated and adhere to safety protocols.

“We…didn’t really realize just how important that was until we couldn’t do it anymore,” Hunt said.

Lent, the 40-day period leading to Easter, traditionally is a time of solemn reflection and sacrifice during which Christians remember the events leading up to and including the death of Jesus Christ.

People often speak of what they will “give up” for Lent.

Since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020, among the most difficult things people of faith had to “give up” was gathering together — and for much longer than 40 days.

Bishop Susan B. Haynes of the Diocese of Southern Virginia, of which the Eastern Shore is part, put it this way in her Feb. 16 Lenten message: “Over the past year we have given up so much — our church buildings, our familiar forms of worship, our frequent face-to-face contact with each other.”

The year has been exhausting and, for many, filled with grief.

Haynes went on to say, “In this state of exhaustion, we are mindful of our own deep need and longing to be restored and reconnected. And perhaps that’s what this Lent should be — a season of restoration and reconnection.”

Hunt spoke about the connection between Easter’s message of hope and what people have been experiencing during the pandemic — and of a way to think about moving forward in these days.

“There is a theological concept — and it was what Paul and his community wrestled with, especially the Galatians,” which seems particularly applicable this year as Christians prepare to celebrate Christ’s resurrection, he said.

Many of the Galatians once they embraced Christianity stopped working and lived it up because they believed Christ’s return was imminent.

But Paul in his epistle to the Galatians called their actions foolish and told them not to stop living and working responsibly in this world while they waited for Christ’s return.

“There’s a concept called ‘the already, not yet.’ The idea of the Resurrection and that Jesus died and rose from the dead and has taken away the sting of death is a reality; it doesn’t mean that there is no longer any death or any suffering. It happened already, but it’s not yet fulfilled,” Hunt said.

Coping with the pandemic at this juncture can be thought of similarly.

“We’re already there — we have a vaccine; we have the means — but we’re not there yet. And it just requires a lot of patience. At a time when our patience is gone, our energy has been sapped, we just have to stay the course — and that’s where community comes in. That’s where people need each other, to encourage each other to keep going,” Hunt said.

Hunt, his wife, Mary, and Mary’s father, Sonny, moved to the Eastern Shore last month from South Dakota.

They may be among the few ministers’ families who arrive who don’t think of the rural Eastern Shore as being off the beaten path.

Hunt’s title during his more than three years in South Dakota was superintending presbyter of the Pine Ridge Episcopal Mission, located on one of the three largest Indian reservations in the United States.

The mission includes nine congregations that were under his care, spread over an area the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Hunt would travel 1,500 miles a month to minister to the congregations.

“That was my parish,” Hunt said.

Before moving to South Dakota, Hunt, a 2002 graduate of the General Theological Seminary in New York City, served parishes in New York and Alabama.

Before going to seminary, he taught English literature at the high school and college levels.

He and his wife have two grown children.

There’s a historic explanation, dating to the mid-19th century, for why the Episcopal church had a major presence in South Dakota’s Native American lands.

Vast swaths of the American West were “kind of carved out through President Grant’s missionary initiative,” Hunt said.

Certain denominations were charged with doing missionary work in certain areas —the Episcopalians were assigned the upper Midwest. The church in the 1850s had started sending missionaries to what was then called the Niobrara district, in what is now Nebraska and South Dakota.

The Episcopal church thrived there, likely because the church’s values mesh fairly well with traditional Lakota ideas about spirituality.

“For example, there is baptism in the Episcopal church; (among the Lakota) there’s a naming ceremony after a child is born and the elders come together and they have a big feed and they say prayers. It’s a lot like welcoming them into the household — which is almost exactly what we (Episcopalians) say…we welcome you into the household of God,” Hunt said.

Similarly, the Lakota coming-of-age ceremony in ways mirrors the church’s confirmation, and there are similarities with other rites, including marriage and funerals.

Lakota culture includes a major emphasis on family. “You can’t let your family down,” Hunt said.

“It was a society which strove for balance — balance with the land, balance with each other. … The destruction of that culture is just tragic,” he said.

COVID-19 struck Pine Ridge hard, making cherished cultural traditions problematic — especially traditions surrounding the death of a loved one.

“In the culture, when someone dies, there’s a two- to three-day wake before the funeral. … It’s part of the honor that you do someone,” Hunt said.

The gatherings include taking meals together, praying and singing together, and sleeping in the same space — activities not deemed safe during the pandemic, even as it resulted in more funerals than usual.

“You don’t judge; you honor the culture; you try to learn the language; and don’t try to change anything,” Hunt said.

Pandemic restrictions also affected Eastern Shore congregations in sometimes heartrending ways over the past year, as funerals were postponed or restricted, among other loss of traditions.

The Holy Trinity congregation has not yet been able to host for the Hunts welcoming events churches typically have for a new minister — coffee hours, potluck dinners, and the like.

Worship services until this past Sunday have been recorded and posted online, with the bare minimum of in-person participants, in accordance with the bishop’s safety guidelines.

It is encouraging that the church is to be able to open for in-person worship for Easter, with safety protocols in place. Last Easter, that was not possible.

And, if there is a bright spot in the changes churches have had to make because of the pandemic, it may be that recorded or livestreamed services online are reaching people wherever they are, even when they are not able or willing to come into the church building.

“I am committed, and the church is also committed, to having online worship, even when all of this is over,” Hunt said.

Living through a pandemic no doubt will have lasting effects on the church as well as on society at large. Some of those effects no doubt are as yet unforeseen, as we work to figure out what the “new normal” will be. Will we shake hands again? Will we hug?

Still, the message of Easter, as it has been for more than two millennia now — is with us. There is hope — the hope of “the already, not yet.”