By Linda Cicoira — John Schoolfield, of Franktown, joined the Marine Corps right after graduating from high school and before he could get drafted in 1965. He served until 1969 and vividly remembers his tour of Vietnam.

It was late March 1968 that 21-year-old Schoolfield came in contact with the Tet Offensive, a series of surprise attacks by the Viet Cong. Those rebel forces sponsored by North Vietnam caused a turning point in the war.

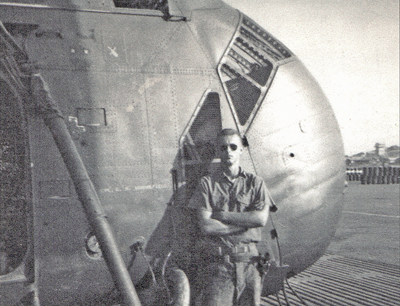

There was still “considerable enemy activity” in the area of I Corps, near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) where he was serving as crew chief of YP-21 stationed at Quang Tri Combat Base, in Central Vietnam.

Schoolfield hailed from Connecticut. His parents were Eastern Shore natives – both writers – Kaatje Hurlbut (his mother’s pen name, sister to artist Babbie Dunnington) and John Schoolfield Sr., a newspaperman, who was raised in Pocomoke, Md.

Schoolfield was with Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 163, or “Ridge Runners.” The unit was well known in I Corps and easily distinguished by the large white and black evil eyes painted on the nose of the aircraft.

“It was my last month in Vietnam and my tenth month as a crew chief,” Schoolfield remembered. “There was a significant combat operation in the process just south of the DMZ, about 15 miles to the north of Quang Tri Base and my aircraft was the day’s designated emergency standby bird to be called upon only if the Marines encountered serious problems and the other aircraft were unavailable. We were the helicopter of last resort.”

Schoolfield’s aircraft was pre-warmed and test-flown that morning for the early afternoon scramble. “As our wheels lifted off the runway,” a pilot advised him about “a significant number of Marines” that had been caught out in the open by artillery fire just south of the DMZ. “Casualties were extensive, perhaps as many as 30 wounded.”

Schoolfield’s task was to take out the wounded, so the remaining Marines could clear the area on foot as quickly as possible as there were no roads in the area and not enough helicopters.

The regular four-man crew had been complemented by a Navy corpsman. “Our pilot that day was a new addition to the squadron and I had not flown with him before,” said Schoolfield. “This mission was clearly high risk and I hoped that he was a skilled pilot. He was a captain, which at least told me that he was likely to be heavy on experience.”

“Just after passing over the Dong Ha Combat Base, the pilot … announced that we were going Lima Lima, or low level, which was standard procedure on an approach in the vicinity of the DMZ.”

This type of approach was necessary to reduce the likelihood of being spotted by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) radar or spotters. “If the NVA knew we were inbound, they could destroy us in seconds with artillery once we were on the ground,” said Schoolfield. “We knew they already had the range and bearing of the beleaguered Marines. An unannounced arrival was imperative for this mission.”

“The pilot shoved the nose down with conviction and flew the bird to the ground, pulling up smoothly about 10 to 15 feet from the deck,” Schoolfield said. “The rapid descent was nicely executed and I was encouraged by this pilot’s skill. We hugged the rolling terrain for several miles until the copilot called out a new heading. Then the pilot hauled the H-34 into a gut-wrenching starboard turn as we dove into a shallow valley which would make us less visible to enemy spotters or radar and help mask the sound of our rotors on approach.”

They barreled down the valley at an altitude so low the rotor wash rocked the scrub brush below. The pilot changed direction suddenly and nimbly, slightly to the left and right, to reduce the odds of enemy snipers drawing a bead on the pilot’s windscreen or nose-mounted engine.

George Schoolfield was crew chief of YP-21 stationed at Quang Tri Combat Base, in northern South Vietnam.

Schoolfield was impressed. As crew chief, he was responsible for loading, defending, and repairing the aircraft. Takeoff weight was extremely critical with helicopters. An overload of as little as a few hundred pounds could cause a crash. The pilot had to have an absolutely accurate weight every time. Schoolfield did a quick assessment and determined they could handle 800 pounds of cargo. He added another 100 pounds based on the cool dense air, light breeze, and pilot skill. The total represented five Marines.

“I could see a half-mile of rolling terrain and a broad expanse of dried rice paddies beyond,” Schoolfield said. The pilot announced “we were inbound with an estimated time of arrived of 1.5 minutes and advised them to standby with smoke … We continued the low and fast approach. About “300 feet out of the landing zone, I hung out the door to watch … for safety as we executed a high-speed low-level landing. It was a fast but perfect landing.” He put his M-60 machine gun on safety and stowed it while scanning the zone.

“What I saw was a scene from a combat Marine’s worst nightmare,” Schoolfield continued. “The rotor wash had mixed the acrid yellow smoke with gray rice paddy dust and rice straw and the gray/yellow cloud swirled around the aircraft and Marines causing an ugly fog. At our two o’clock, beside a 2- to 3-foot rice paddy dike, were two wounded Marines being flailed unmercifully by the corners of the ponchos on which they were lying. The olive drab of their fatigues contrasted sharply with the white bandages stained red with blood.”

At three o’clock, the radio operator kneeled, head down, as he communicated while trying to shield his face and eyes from the flying straw and grit. There was not a firm number of wounded.

Schoolfield considered the possibility of overload. He could either dump the center fuel tank, which would take four or five minutes and was the most dangerous, or risk a rolling takeoff which could take as much as a mile but could add another 400 to 600 hundred pounds of capacity.

With a warren of rice paddy dikes 200 to 300 feet apart and pocked with shell craters from the artillery barrage, he thought the latter option would be very difficult or impossible.

“I saw the first wounded Marine approaching from the rear,” said Schoolfield. He was tall and thin and was being supported by a comrade.

“I dropped to the step and helped him through the door noticing he was standing on the side of his right boot. His foot was cocked off to the side. Despite his shattered ankle, he seemed oblivious to pain,” Schoolfield noted. “I motioned for him to sit in the jump seat. He shook his head with conviction indicating he wanted to stay by the door and help his fellow Marines as they entered. I shrugged and allowed him to stand as we took in a medevac who had a horrible abdominal wound. His face was pale and his breathing was shallow but he was alert enough to look around the aircraft. The gunner, the doc, the tall marine, and I took the four corners of his poncho and gently placed him crossways in front of the window. I kneeled beside him, raised his head, and placed a soft cargo strap under it so that the side of the vibrating aircraft would not cut into his scalp.”

The two badly wounded that were first spotted, and another with equally threatening injuries, would have made a full load. But two more were brought up on the left side.

“There was no discussion of the risk of a takeoff with an overload—we all knew the risks and this was what we had to do,” Schoolfield said. “I slid the legs of the three forward wounded aside and we carefully placed the torsos of the two Marines in the small open space and lapped their legs over the hips of the others doing our best not to cause them further injury or restrict their breathing. Another medivac was brought in from behind the aircraft and we were able to squeeze him in.”

“I turned back to the door and to my disbelief, there was yet another wounded in a poncho being held in the arms of another Marine. I frantically scanned the cabin but there was no usable space left. The only option was to strap him into my chair by the door and stand in the doorway for the return flight.”

Schoolfield and the tall Marine hauled the last wounded man to the door. “To my horror, the Marine’s head rolled from his shoulders into his lap. After recovering from the shock, I slid the soldier back into the arms of the Marine on the ground, dropped down on the step, placed my arm on his shoulder and shouted to him that we were badly overloaded and could not take his friend at this time because he was dead. He simply stared at me with glazed eyes —uncomprehending — clearly in shock. Mercifully, two fellow Marines appeared, quickly assessed the situation, and helped their comrades away from the door.”

“We were so grossly overloaded I couldn’t take a risk for one who had died,” Schoolfield said, adding, another helicopter was sent.

With eight wounded and one corpsman, Schoolfield reached down for his wire cutters preparing to ask to dump fuel. “The Pilot gave me quite a shock as he quickly brought the rotors and engine up to full power and gingerly raised the aircraft on her struts as if to test the weight of the load.

The pilot started rolling the H-34 forward toward the upwind rice paddy dike and simultaneously lifted the tail of the aircraft into the air creating a nose-down attitude—- like a wheelbarrow. As he accelerated towards the first dike I took a deep breath—and held it. I then understood his plan—he was going to use the momentum in the spinning rotor blades rotors for a brief moment to hop over the rice paddy dike. We couldn’t fly, but we could leap.”

“I kept my head out the door watching as we reached the first dike at about 10 mph and made the hop—we cleared the dike by a foot and accelerated to the next and cleared it as well. We continued to accelerate and the hops became faster and faster … We reached what I estimate must have been 50 mph and were jumping every four or five seconds sometimes clearing the dikes by mere inches. Finally, after leaping over at least a dozen paddy dikes we cleared one at perhaps 70 mph, took a single bounce, and stayed airborne at about six inches above the ground. We raced towards the final paddy dike, lifting slowly and cleared it by less than a foot. The venerable H-34 gained speed and lift rapidly after clearing the last dike and the pilot pulled YP-21 into a sweeping left turn as we headed for Dong Ha’s Delta Med.

“I blasted out a lungful of air and gasped for breath, realizing that I had held my breath through this entire, truly remarkable, takeoff. Not a word was spoken by the crew or pilots. We simply flew towards Dong Ha, amazed I suppose, that we were still alive and were able to bring all of our Marines home. It was my 13th and final month in Vietnam and I had never heard of a takeoff like this one ever.

“The doc and I arranged, untangled, and shut down the numerous IV bags as we approached Dong Ha while the tall Marine crawled around the cabin and comforted his fellow Marines with a hug a handclasp or a thumbs up. Not a single Marine complained about their wounds or the way they were packed into the crew compartment.”

The landing was solid and the wounded were taken into the field hospital. Another man did not survive. Schoolfield reached out to shake the tall Marine’s hand. “But instead he threw his arms around me, gave me a bear hug and began to sob. Tears poured down his face carving pink rivulets in the gray rice paddy dust. ‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Thank you all for helping my friends.’ I replied that it was he and his fellow Marines should be thanked after what they had been through and survived on that day.”